“The GEG is a step in the right direction”

In November 2020, Germany’s Buildings Energy Act (GEG) came into effect with the aim of expediting the energy transition in the buildings sector. In an interview for Zi, Prof. Dr.-Ing. Andreas Holm from the Forschungsinstitut für Wärmetechnik München (FIW – Heat Engineering Research Institute in Munich) explains what this means for brick building, the predominant building method in housing construction. He sees both positive and less positive aspects in the new Act. Although the GEG does not contain much new for the time being, it points the way to more energy efficiency in the future.

ZI: The objective of the GEG is to ensure more climate protection in the building sector. Do the new regulations achieve this?

Prof. Holm: Yes and no. The Act can in any case make an important contribution to achieving it, but probably not until version 2.0 comes out. With regard to many aspects, it doesn’t say anything different than the regulations that we have had up to now – especially in housing construction. For example, the requirements from the Energy-Saving Ordinance 2016 (EnEV) or the Act on the Promotion of Renewable Energies in the Heat Sector (EEWärmeG) have been retained in the GEG. But looking to the future, the Act is certainly heading in the right direction.

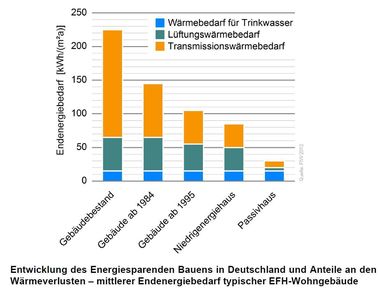

Prof. Holm: In principle, every newbuild causes CO2 emissions – regardless of how low these may be. For that reason, it is prudent to ensure in the long term and in the medium term, respectively, that the carbon dioxide emissions of a newbuild are minimized both during its construction and in its usage phase. That is because what I do today will endure for a long time. The lifetime of technical construction materials usually lasts several decades – in the case of load-bearing elements like, for example, brick masonry, we are even talking around 100 years. So it is judicious to commit to low-CO2 energy sources now. At the same time, it is necessary to ensure that these are permanently available in the required quantities. After all, CO2-neutral does not mean the same as energy efficient. A poorly insulated house that is heated with wood would be climate-neutral as wood is CO2-free by definition. However, for this you would need around 1.5 hectares of sustainably managed woodland. For this reason, it is important to take an integrated approach to energy efficiency. In my opinion, in the future it will be very much about how we manage renewable energies. Here, the building envelope and the building method play a key role.

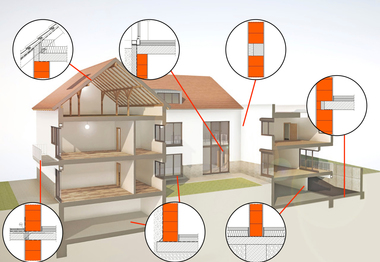

Prof. Holm: I don’t believe that our energy requirement as it stands today can be covered exclusively by renewable energies. Therefore we have to massively reduce the energy required for the running of the building, too, and achieve a saving of at least 50 percent to realize the climate goals for all the different sectors. The GEG is, however, a step in the right direction in this respect. Above all, it is important that with regard to the building envelope, we have not eased up on additional important requirements. An example in this context would be heat insulation. For the building envelope ensures that we rationally manage the available quantities of energy.

Prof. Holm: Basically, the GEG does not say anything new for the building envelope as it is essentially the same as EnEV 2016. However, requirements for the future have also been set out in the Act. For example, from 2023, we have to take grey energy into account. At the present time, this does not yet have any consequences, but, of course, it will soon play a part. This also applies to any tightening of the regulations that may possibly be imposed on us.

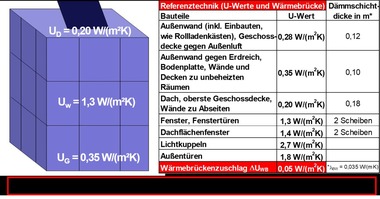

Prof. Holm: In comparison with EnEV 2016, in the GEG everything has stayed the same, too. From my perspective, it should not be forgotten in this connection that it is important for the building envelope not just to focus on reference values. These are contained in the Act, but the requirement is only that the overall thermal protection is fulfilled. The reference values are guidelines. With “poorer” U-values than the reference technique states, the thermal insulation of the building envelope can be achieved without any problems. Ultimately, it is not a matter of the individual elements, but an overall approach. In combination with all relevant building elements – like, for example, the windows or the roof – thermal insulation can be easily achieved with monolithic brick building.

Prof. Holm: I expect in any case that the regulations will be tightened up. We are probably moving towards Efficiency House Standard 55 – perhaps something a little less. From the perspective of masonry representatives, this is certainly easily doable. If, in addition, the CO2 prices are taken into account, an Efficiency House Standard 55 would probably not be uneconomic for masonry building. It works with conventional wall thicknesses – also with cost-optimized models. After all, half of all subsidized detached and semi-detached houses correspond to KfW-Efficiency House Standard 55 or even better. That is, today many particularly energy-efficient buildings are built with solid masonry. In monolithic brick building, building owners can erect buildings with higher efficiency classes like 40 Plus or even passive house standard. For the construction of apartment buildings, however, a more differentiated evaluation is required: here the focus cannot be only on energy efficiency, but also on aspects such as, for instance, load-bearing capacity. It is therefore necessary to discuss whether we should be aspiring to Efficiency Class 55 for multistorey buildings. Ultimately, especially monolithic building takes a large share here.

Prof. Holm: For the start, again little is changing in this respect. In the case of a tightening of regulations, we are probably getting closer to KfW Efficiency House Standard 55, although with slight changes. The German government could then introduce a new subsidy level if necessary. We shall probably end up with a solution in which with regard to the primary energy requirement, the standard is KfW-55, but slightly less for the building envelope. The Efficiency House Standard 55 would consequently remain eligible for subsidies in the KfW. With the last tightening of the regulations, this is how it was done and in my view, it is a prudent approach.

Prof. Holm: In respect of the energetic quality of the building, the requirements have actually stayed the same since 2016 and yet the costs have risen nevertheless. There is therefore no direct link. The main cost rises don’t tend to be for the building envelope, but far more these are associated with the building equipment and technology – for instance, because of ventilation systems, heat pumps or low-temperature systems. The requirements of the new GEG, however, don’t make building any more expensive.

Prof. Holm: In my view, the GEG is confirmation that brick building is still sustainable for the future. The industry has the technologies to meet statutory requirements now and in the future, too. Naturally, there are challenges – however, less on the technical side as the different brick manufacturers have corresponding efficient products available. It is possible with the existing technologies and accordingly solutions can be found for a GEG 2030, too.