Customised solutions for colours and effects

Vitreus GmbH was founded ten years ago and has developed into an established supplier of engobes, granulates and glazes as well as raw materials. To mark this milestone anniversary, the ZI editorial team paid a visit to the company in Seevetal, south of Hamburg. In an interview with Joachim Grothe, Managing Director, you can find out, among other things, how the colour gets onto the brick and why this requires both tailor-made solutions and sometimes controlled misfiring.

1. Markets

We met at the Clemson Brick Forum last year. How important is the American market for Vitreus?

Joachim Grothe: The American market is important to us because at the end of the day it’s the only growth market. We are seeing declines across Europe. But these are within a tolerable range compared to the catastrophe that is happening in Germany. That’s why it’s currently helping us a lot that a large part of our sales have been and continue to be generated outside Germany.

North America is strongly characterised by the idea of a “housing ladder”, the gradual acquisition and sale of properties of increasing value and quality.

This keeps the housing market and construction activity going. The market in Australia, which is Anglo-American influenced, is similar. Even if it is relatively small, with a population of around 26 million. We have another small, fine market in South East Asia. But not much is being built there either at the moment.

So are you worried about market developments?

JG: In addition to the sometimes difficult market environment, we are particularly concerned about the trend towards consolidation and acquisitions in the industry. This is because the big players, as can be seen in the German brick and tile industry, are focussing more on vertical integration. Given the choice between their own or an external solution, the internal solution is almost always favoured. For this reason, a takeover such as that of Creaton and Terreal by Wienerberger AG is not a good sign for our small niche sector.

2. Challenges of colour production

What is the challenge in colour production?

JG: There are many factors to consider. For example, with roof tiles, the aim is to achieve a glaze that is as flawless as possible. First of all, this means that the colour must have few pinholes and be stable in the kiln. In addition, the gloss and colour tone of each roof tile must be identical across the cross-section of the kiln. The glaze must withstand temperature changes without cracking. To do this, we heat the roof tile to 180 degrees Celsius and put it in 20 degrees cold water. Then we test the colour for acid behaviour and abrasion or hardness. Finally, the colour must not cost too much. We first test all of this in preliminary tests in our laboratory. But the truth is in the customer’s tunnel kiln. The colours have to prove themselves there.

That sounds like the opposite of trivial. Is this effort necessary?

JG: I can give you a striking example that is well-known in the industry. A roof tile manufacturer once received a black glaze from a colour supplier. However, the finished black glazed roof tiles first became lighter in colour on the roof and then partly whitish. This resulted in damages running into millions. Since then, the industry has been very cautious.

The cause of this unintended colour change was the interaction between a component of the clay mixture, calcium, which was present in abundance in this case, and acid rain. Calcium and sulphur react to form calcium sulphate. This substance is not hydrolytically stable. After formation, the calcium sulphate or anhydrite was deposited in the layer between the engobe and the body. The leaching of the anhydrite created small tunnels that influenced the refractive index of the engobe in such a way that the bricks shone brightly.

This chemical reaction was not foreseeable?

JG: It was probably not possible to predict whether the proportionate amount of calcium present in the clay mixture and glaze would allow this reaction and to what extent. This is because every roof tile manufacturer has its own mixes and its own target value for calcium in the coatings they use. Each roof tile manufacturer therefore has its own specifications for the engobes and glazes. The tile raw material is too complex as a material and building ceramics are exposed to too many different influences to be able to simply calculate a reliable engobe or glaze in advance. Too many factors influence the final result: the desired colour and effects, the composition of the clay and engobe, the production processes, environmental influences, etc. In addition, none of these aspects are completely constant. This is why processes in ceramics do not take place with precisely defined values, but always within a corridor.

So you have to constantly adapt your products?

JG: That’s the case. The clays, raw materials and sources of supply are changing, as are the equipment and tools, so our colours have to, too. In ceramics, there is a quasi-Buddhist basic insight: the only constant is change. You could also compare our work to bespoke tailoring. The suit has to be made wider after Christmas and narrower again in the summer.

For example, we developed a very successful surface colour for a customer a few years ago. It is now in its third generation. It was originally about the quality of the paint application. Then there was frost damage that had to be addressed. Now we have made the colour even harder. I can’t say what the next change will be. But I know that it will come. For us, our products are not just materials, but ongoing, constantly changing processes.

Does this mean that you have to provide service virtually all the time?

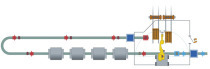

JG: The nature of the business makes this essential. Consistent colour quality can only be guaranteed by constantly balancing out fluctuations and implementing changing requirements appropriately. This is only possible by constantly developing, producing and providing service by our ceramic experts and engineers on site. That is why these coatings, glazes and engobes do not come from China, for example. That won’t happen either. We have to be on site all the time to be able to provide the service. A good example of this is the spray booth. The colour application in the spray booth differs from customer to customer and from country to country. If our paint is to be sprayed, we have to check the customer’s spray booth on site and often adjust our paint accordingly.

Our employees are often regularly on site for months at a time for preliminary tests and fine adjustments. One of them is currently in a plant at least three days a week to adapt a colour to the production conditions. Trials have to be carried out, then a factor has to be changed slightly, then the flow behaviour has to be adjusted, and so on and so forth. The partnership can sometimes even go so far that our employees are also asked about other aspects of production. They also help if they can. Because we see ourselves as a dynamic interface.

3. Trends and prospects

What trends in heavy clay surfaces do you see currently and in the coming years?

JG: Originally, the brick industry was all about the most uniform possible quality and appearance of bricks. For several decades now, the market has been moving in exactly the opposite direction - the demand is for everything but uniformity. This places special demands on us, namely to develop controlled processes for an uncontrolled appearance. At the end of the day, we work with our customers to develop controlled misfires.

A few examples: For a producer of facing bricks in the USA, we are currently developing a production process in which three colours are applied plus a scattering granulate. This results in an appearance that takes some getting used to for typical German tastes. But there’s no accounting for taste. In the USA, this is a top product.

Another trend in the USA is rustic effects on the brick surface. The older the better. Smooth surfaces like in Germany are less in demand there.

We are also working on alternatives to coal firing. Coal-fired optics are currently in high demand on European markets, but coal in the kiln should be avoided due to the associated climate-damaging emissions. That is why we have developed an extensive range of coal firing that produce the same marks on exposed bricks as coal firing, but without emitting CO2.

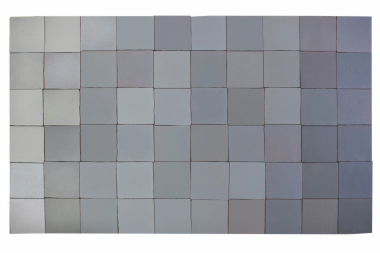

Finally, good white or very light surfaces in light grey or cream are in great demand. These colours are already very popular in Scandinavia and Germany. The challenge with white or light colours is that the surfaces coated with them get dirty very quickly. In order for regular cleaning to take place, the surface must be abrasion-resistant. This technical and qualitative optimisation is not easy, especially with ceramics. We have developed an off-white colour that becomes very hard when applied. We are currently researching how the colour remains beautiful. The colour is very popular in America at the moment.

This is followed by another increasingly important topic: cooling colours. This involves colour applications that at least partially reflect thermal radiation. This means that appropriately designed surfaces heat up less. These include white and light colours. However, there are also approaches for reflective surfaces in dark colours. There is great potential for this in India and countries with rising temperatures, where people are confronted with 50-degree heat without expensive technical aids.

How do you see the future of brick?

JG: The building material has lasted for over 2,000 years. The next 50 years will not be able to make it disappear, no matter what laws or CO2 regulations are introduced. But it is possible that single-family house construction will not reach the same level as two years ago. Building costs will not fall. So the political attitude towards single-family house construction would have to change again. Whether this will happen is unclear. What will save the building material and some of the manufacturers through the current crisis are renovations to the existing brick stock. Because we cannot afford to let these houses fall into disrepair.

4. The company

Why did you decide to found Vitreus ten years ago?

JG: We, five colleagues from the industry, decided at the time to do something of our own. The staff joined us over the years. Our aim was to work the way we wanted to. Flexibility was particularly important to us.

At the time, we kept a very close eye on the market and realised that there was a need for a new player in heavy clay ceramics. The company takeovers and the disappearance of well-known names in recent years are proof of this. We also focussed on markets outside Germany, particularly France, right from the start.

The company name Vitreus, the Latin word for glass, is intended to express the standards we set ourselves. The industry is very secretive in all respects. We want to set ourselves apart from this and communicate as openly and transparently as possible, both internally and externally.

Where do your colours come into play?

JG: A fine and current example stands in Paris. There, we are currently working with a customer on rustic renovation bricks for the reconstruction of Notre Dame after the fire. Like many others involved, we are making our contribution without pay. The reward is to be proud that we can work on such a project. It is also the result of ten years of hard work.

What is the basis on which Vitreus has achieved this development?

JG: The whole thing only works with very good employees. Fortunately, I have a qualified and committed team that I can rely on, including eight ceramic engineers and master craftsmen. That’s a relatively large number for our small company and more than work in some brick companies. But this expertise is indispensable for our products and our service. What we lack here in Seevetal near Hamburg is specialised personnel, such as experienced production staff. They are difficult to find anywhere in Germany. In the Hamburg suburbs, where the competition is Airbus, for example, it is even more difficult.