The Heisterholz brick factory (Minden, Germany)- Contribution to its 150th anniversary

The Schütte AG Heisterholz brickworks was one of the most important brick manufacturers in northwest Germany at the beginning of the 20th century. The company has left its mark on the region and the people, especially in the Minden area, to this day. Houses and street names bear witness to this. The products, bricks, were used in buildings throughout northern Germany. Finally, it also left its mark on the family of the entrepreneur Ferdinand Schütte. He laid the foundation stone for the Heisterholz brick factory 150 years ago. Renate Nöller, great-great-granddaughter of the founder, traces this history in the following article.

The small village of Heisterholz is situated near Petershagen, not far from Minden, directly on the Weser. In marine sediments of the middle Lower Cretaceous, layers of clay several metres thick are found here, interspersed with harder clay-iron stones. The first clay pit of the Heisterholz brickyard was located about three kilometres south of Petershagen.

Individual brickmakers who made use of the deposits are mentioned in 1724. After the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), a settlement was made under Frederick the Great to promote trade in the region. Heavy ceramic goods and bricks shaped into shells were produced.

If you come to Heisterholz from Minden today, you will be guided to the brick factory by signs pointing to an industrial site. A huge area with large industrial sheds towers over individual, older red brick buildings. A desolate house becomes visible at the western edge (» Fig. 1). A former veranda leads to a park-like garden with old trees and a pond. The remains of a fountain, the iron frame of a swing and a Chinese-style tea house, decorated with beautiful wood carvings and filigree rusty railings, hint at times gone by. It is the original home of the owner of the Heisterholz pottery factory.

Foundation of the Heisterholz steam brickworks

In 1873, at the end of the founding years of the German Empire, the timber merchant Ferdinand Schütte, descended from a local carpenter family, together with the master bricklayer Theodor Wiese, acquired the hand-moulding brickworks founded in 1858 by the brothers Wilhelm and Friedrich Rümke at the clay pits of the Weser in Heisterholz, which became the property of the farmer Christian Barner in 1866 (» Fig. 2).

It was the age of industrialisation, the rural population moved to the cities to work, the demand for housing increased, and the stones needed for building became scarce. In order to produce larger quantities of bricks, the brickyard was soon converted into a state-of-the-art factory with steam operation and given the name “Schütte & Wiese, Dampfziegelei und Thonwarenfabrik, Heisterholz”. The first 37-metre-high chimney was erected.

Prussia’s numerous building projects caused the demand for bricks and roof tiles to increase considerably. In response, production was expanded and the factory enormously enlarged. The migrant workers from Lippe and East Westphalia who were employed at the brickworks increasingly settled in the area. On the factory premises they could move into a factory flat in a workers’ colony that was exemplary by the standards of the time. There was a warm common room and a washroom. With the exception of public holidays, they worked up to 16 hours a day. Wages were paid in cash every 14 days on Saturdays. As a result of the social laws enacted by Bismarck, a separate company health insurance fund was founded on 18 November 1884, in which all workers who did not belong to a recognised health insurance fund were insured. On the occasion of 25 years of service, employees were honoured with a memorial page and a commemorative coin from the Association of German Clay Industrialists as well as a savings book and a recliner. With the introduction of the twelve-hour day in 1906, working hours were set from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m. with a one-hour lunch break. A workers’ welfare building with a dining hall, lockers, heating, bathing and showering facilities was built, and in 1912 a company-owned estate with 203 acres of land and farm buildings were added. The cultivation of the farm’s own fruit and vegetables ensured the food supply of seasonal workers in winter, so that they could stay all year round. Schütte also promoted the building of homes with gardens. By 1913 the settlement had grown to 32 houses and had its own waterworks.

Ferdinand Schütte’s family lived according to their station. The children received a middle-class, Christian-humanist education. Martha entered the daughter’s school in Minden on 1 April 1874. On the occasion of her engagement to the royal district administrator Theodor Parisius and that of Louise to the doctor Dr. Otto Sonnenburg, a large celebration took place in Heisterholz in May 1890. Martha’s wedding was also celebrated here. Their dowry, documented in a book in 1891, was lavish. They lived briefly in Zabrze/Upper Silesia, where their only child Martha (3.9.1892-3.9.1964), named after her mother, was born. Barely three months later Theodor died and the young widow returned to her parental home (» Fig. 3).

On the road to success

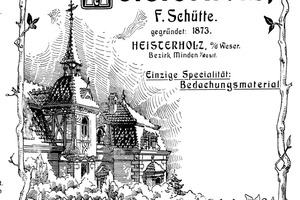

In the same year, in April 1892, the business partner Theodor Wiese left the company, so that the business became the sole property of the Schütte family as “Dampfziegelei Heisterholz F. Schütte”. Ferdinand Schütte was a respected industrialist and factory owner in the area. When his brother Hugo, who worked as an authorised signatory in the brickyard, died, the mayor and the town council of Petershagen expressed their condolences in a letter dated 20 May 1896.

The bricks were distributed on the Weser as far as Bremen and on to Schleswig-Holstein. The coal needed for firing also reached Heisterholz via the Weser. On land, horse-drawn carts were used until 1898, when the Minden-Uchte district railway was inaugurated with a great ceremony. The construction of a loading station one year later on the route to Plant I made it possible to ship coal and bricks by rail. This made overland transport much easier. Shipping was faster and less goods broke compared to the journey over the bumpy roads.

In 1898, the brickyard also celebrated its 25th anniversary with fir tree decorations. The business was flourishing. Instead of being made by hand, the bricks were now shaped by brick presses using the latest technology, and ring kilns were introduced. The children were the first to light them. The hot exhaust air was used to dry the bricks, so that the bricks were not blasted by frost in winter and year-round production was possible. All the bricks and roof tiles for the houses in the area were made in Heisterholz.

Traces of success

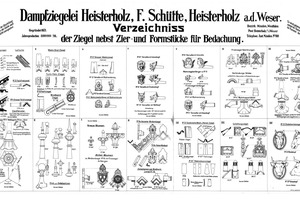

The economic success of the production led to supra-regional orders, also for custom-made products (» Fig. 4). For example, the bricks for the Oberhausen railway station, the Hamburg electricity works, the figures on the Henrietten-Stift in Brunswick and the mosaic floor of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin all came from Heisterholz. In 1889, the German imperial couple visited Minden to attend an army manoeuvre. At the reception, Ferdinand and his brother Max Schütte were present as Minden’s city councillors. Ferdinand presented the Emperor with his request to build a canal to the Ruhr area. The Emperor showed particular interest when he pointed out that the canal would also be advantageous for the increasing construction of barracks.

Ferdinand received awards for his selfless and long-standing commitment to the volunteer fire brigade. Since the brickworks’ firing system meant that large fires often occurred on the company premises, he had been a member of the Minden-Ravensberg-Lippe Fire Brigade Association since 1873. On 3 July 1898, the association awarded him a service diploma on his 25th anniversary. On 12.9.1889 he was awarded the Order of the Crown, 4th class, and on 15.2.1909 ‘By Order of His Majesty the King’ the Order of the Red Eagle, 4th class.

From 1913 onwards, fire water could be taken from the 23-metre-high tower of the waterworks built for the workers’ settlement (» Fig. 5). This has a special 12-cornered “lantern roof” construction with glazed roof tiles, at the corners of which are stone lion and wolf heads. In winter, the tower was heated with coke on an open hearth so that the water pumped up under pressure in the tank would not freeze.

For his widowed daughter Martha, Ferdinand made the decision that she should raise her nieces Anneliese and Paula, who had been orphaned after the death of her sister Louise and her husband. For this purpose, in addition to the necessary financial support, she received a villa in Minden at Wilhelmstrasse 1 on 2 May 1905. The children were educated privately. Martha also enjoyed travelling with her daughter and staying in fashionable hotels with illustrious guests.

Their son Fritz, who had already succeeded Hugo Schütte in 1896 at the age of 22 and had become a partner in the brickworks in 1899, was put in charge in 1905. He married and had four children: Hans (1907-1975), Fritz (1911-1973), Katharina (1915-1985) and Ferdinand (1917). He also received power of attorney for the will written by Ferdinand and Pauline on 10.2.1911, in which all children inherited in equal shares. The inheritance share from the deceased Louise was given to her children Anneliese and Paula.

Further growth

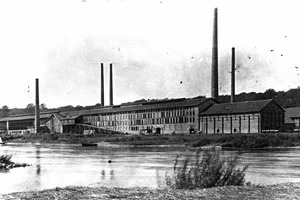

The brickworks had grown enormously around the turn of the century (» Fig. 6) and was the third largest employer in the district of Minden. The company’s own ferry provided fast access to the factory premises. In 1910, factory II, a clinker factory, was built. The factory site, which by then had five chimneys, two new kilns, seven drying sheds and a large warehouse, had doubled in size (» Fig. 7, » Fig. 8).

In 1912, another factory, Factory III, was built in Holtrop with its own jetty. 10 million roof tiles and 5 million bricks were produced annually. In addition, a track was built as a connection to the Minden-Cologne railway line. The number of workers grew to 400 in 1914, and the owner Ferdinand Schütte was one of the richest citizens of Minden.

The town developed into an important business location. Between 6 June and 6 September 1914, a trade, industry and art exhibition was held there. For this purpose, the brickworks presented photos of well-known buildings constructed with Heisterholz bricks in an octagonal pavilion constructed with bricks in various patterns and colourful roof tiles (» Fig. 9). As the most important brickworks in north-west Germany, the brickyard was awarded a golden memorial coin.

Minden was a garrison town at the time. Max Schütte and Hans Nöller (12.10.1880- 21.2.1958) served in the field artillery regiment 58 stationed there. The latter came into contact with the young Martha. When she was staying with her mother in St. Moritz in Switzerland, Hans sought her out and asked for her hand in marriage. In October 1913 the wedding took place. They moved into a flat at Blumenstrasse 9 in Minden and received a lavish trousseau with custom-made furniture, the finest linen, valuable Rosenthal porcelain and family silver with an engraved N. A few months after the honeymoon, the outbreak of the First World War separated the young couple. Hans went off to war and was taken prisoner in France. In 1918 they met again in Minden.

Even during the political turmoil of the First World War, the Schütte family led a very middle-class life. Ferdinand and Pauline lived in a stately city villa at Hahlerstr. 33 in Minden. On 11 October 1914 they celebrated their golden wedding anniversary, for which they received a personal letter of congratulations from the city of Minden.

The First World War and the time of hyperinflation

The family was also involved in charitable work. Between 1911 and 1918, Pauline responded to an appeal for donations by the local poet Peter Rosegger to build a forest school in Styria. The family members supported Hindenburg and participated in the exchange of private gold for iron jewellery. For example, Pauline’s daughter Martha sold gold jewellery on 4 June 1916 and 23 July 1916 to “strengthen the military power of our German fatherland”. On 7 March 1917, she donated three quarters of the meat from a pig she had slaughtered. As part of the moral support of the troops by the civilian population, so-called “Liebesgaben”, she made contact with a German prisoner of war in Japan.

Ferdinand Schütte lived to see the great success of the brickworks run by his son Fritz. He died on 2.1.1917. In March and August 1917 the heirs were listed in writing as community of property at the Petershagen district court.

Since production figures also increased enormously during the First World War due to orders for the construction of private houses, state administration and school buildings as well as industrial plants, Fritz considered it appropriate to purchase another brickworks in 1918, Plant IV in Dehme near Bad Oeynhausen (Schütte AG Dehme ‘Porta Westfalica Plant’). Ten kilns now produced about 50 million bricks a year. The economic success created a need for more space and representation. The brickworks’ headquarters were moved to Minden in 1919 to larger and better premises at Marienstraße 36 and later to Marienwall 8. Max Schütte (1878-1961), who was responsible for representing the brickworks, had already taken over the office of a timber merchant with carpentry and furniture factory run by his father, the master carpenter Fritz Schütte (1857-1919), a brother of Ferdinand, since 1875. He worked as a building contractor until 1906 and was a member of the town council and the general assembly of the former Minden Chamber of Commerce until 1914. On the board of the non-profit housing corporation, he promoted social housing construction - probably also that of the brickworks.

In order to be able to invest in new factories, Fritz took out large loans based on the excellent balance sheets of previous years. However, the good clays of the deposits in Heisterholz were gradually depleted. The now harder clay slate with pyrite deposits required a new manufacturing process for bricks and clinker. In addition, there was a shortage of coal due to the loss of the Upper Silesian sources of supply, so that the firing of the kilns had to be converted to peat as fuel. Despite the adjustment of the production conditions and the technically very well equipped brickworks, it was soon no longer possible to repay the loans taken out for the new works. As a result of inflation, which increased significantly especially in the post-war years, there was a massive drop in orders and paying the workers, which was now done on a daily basis, became increasingly difficult. Finally, Fritz saw no other option than to convert the industrial enterprise into a joint-stock company, the ‘Schütte AG für Tonindustrie’, on 16.6.1922. Still loyal to the emperor, a bust of Kaiser Wilhelm was produced for the occasion with a signature ‘Schütte AG’ on the back. The largest share of the shares was divided among the siblings and thus remained in the possession of the family.

The family, richly endowed financially with the huge factory facilities (» Fig. 10), wished for nothing more than the return of the Empire, which had ended in 1918. In 1918, Martha Nöller’s first son, Ferdinand’s great-grandson, Hans-Georg, my father, was born. In 1921 Martha travelled to Zabrze/ Hindenburg in Upper Silesia to take part in the vote on whether her birthplace should remain in Germany. In the same year, her second son Friedrich was born.

At that time, the family was still relatively well off materially. The young Nöller family spent holidays together with their grandmothers and a nanny on various North Sea islands: Amrum in 1923, Helgoland and Sylt in 1924, Baltrum in 1926.

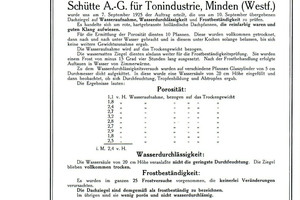

The quality of the bricks that could be produced was examined in a chemical laboratory in Berlin in 1925 (» Fig. 11). In the 1920s, numerous modern buildings such as the Hansa Tower in Cologne (1925) (» Fig. 12) or the Düsseldorf Police Headquarters (1926) were built with the bricks, which were described as being less porous, frost-resistant and impermeable to water; the diversity of the range was presented in brochures.

The decline and sale

As a result of the hyperinflation that reached its peak in 1923, Fritz Schütte was soon no longer able to hold on to his shares as the main shareholder. In 1926, the prosperous company faced bankruptcy and had to be sold. The money had a fixed value again, but the debts, which amounted to millions, could not be repaid. The banks did not want to give any more leeway either. The enormous shareholding that Martha, Paula and Anneliese had inherited in addition to the real estate that Ferdinand had divided up fairly in his will finally lost its value with the insolvency of the company.

The business was taken over by Otto Heurer on 20.2.1926 as ‘Schütte OHG’. In 1928 the brickworks was represented at the exhibition for industry, construction and housing in Hanover. It received the Golden Medal and the Honorary Award of the Building Trades Office. Orders during this period included the construction of the high-rise building of the Rolandmühle in Bremen (1927), the Lengerich railway tunnel (1928), the Hindenburg lock in Anderten (1928), the Hindenburg monument on Helgoland (1929), and the Dortmund pedagogical academy (1929). The main office of the four works of the ‘Schütte Akt.-Ges. für Tonindustrie’ was now located at Stiftstr. 31 in Minden. In 1929, the ‘Schütte KG a. A.’ was continued by Ernst Rauch, Heurer’s son-in-law.

Ferdinand’s daughter Martha remained very close to her daughter Martha. Their son-in-law Hans was no longer in demand professionally as a retired major after 1923, which additionally deprived them of their upper middle-class livelihood. In 1927 they decided to move to the countryside not far from Heisterholz in Frille 54. To buy a house, Martha Parisius took out a mortgage on her villa in Minden and moved with her on 10 February 1928. Thus they had rental income and were able to live off their own chicken farm until 1937, when Hans again served as an officer shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War.

With the brickyard, their carefree world was lost, which finally came to an end in 1940 with the death of Martha Parisius. After the war, Martha and Hans Nöller were no longer able to move to Minden into their villa in Wilhelmstraße, which was occupied

by refugees. Nor was there any food supply from the brickworks estate or even a place to live on the factory premises. They found makeshift accommodation in Göttingen with Hans’ sister. They received food from Switzerland through their former contact in St. Moritz. After a few years they decided to build a small house on the Wilhelmstraße site and approached the brickworks with a request for a loan. Referring to her grandfather Ferdinand Schütte, Martha finally received a loan from the Minden savings bank. In the same year, on 1 March 1955, after 82 years, the brickworks was renamed ‘Tonindustrie Heisterholz Ernst Rauch KG’. In 1956, at the age of 64 and 76, Martha and Hans were finally able to return to their beloved Minden, where they spent two more years together before Hans died.

Aftermath

Throughout their lives they felt a deep connection especially with Ferdinand Schütte, but also, like many locals, with the brickworks. The family grave laid out by Ferdinand and Pauline in Minden is protected as a monument by the town. Near the Heisterholz brickworks, Ferdinand-Schütte-Straße and Fritz-Schütte-Straße recall the importance of their founders for the region.

From 1984 onwards, the brickworks belonged to various companies, such as Brandenburger Dachkeramik (1997), Rupp Keramik (2000) and finally Braas, Lafarge, Monier, which has been known as the Brass Monier Icopal (BMI) Group since 2010.