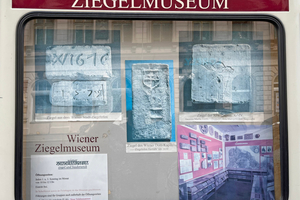

The trace of bricks – A visit to the Vienna Brick and Building Ceramics Museum

You can follow the trace of bricks at Penzinger Straße 59 in the district of the same name in the Austrian capital Vienna. The Penzing District Museum and the Vienna Brick and Architectural Ceramics Museum are housed in a former office building. From the outside, there is little to suggest that behind the door is one of the most extensive collections of bricks in Central Europe. ZI editor-in-chief Victor Kapr visited the museum in July 2024 and met museum director Dr Gerhard Zsutty for a guided tour of the exhibition and the history of bricks and brickworks in Austria and the territory of the former Habsburg Monarchy. He also discussed in detail the activity of tracing and interpreting the signs of the bricks. There were also exciting and anecdotal facts from the history of Wienerberger and a knowledgeable overview of the history of brickmaking and technology, as if we were leafing through Willi Bender’s “From Brick God to Industrial Electronics Engineer”. Read on to find out why a visit to the Vienna Brick Museum and a conversation with its director are worthwhile for friends of bricks and brickworks. The ZI editorial team would like to thank Manfred Zeilinger for pointing out the museum.

A place for collecting and preserving evidence – about the Vienna Brick Museum

History of the Vienna Brick Museum

It is thanks to Anton Schirmböck (1898-1982), who is also regarded as the founder of brick research in Austria, that there is a museum for bricks in Vienna at all. The primary school teacher came to this subject through his hobby of archaeology. During excavations, he repeatedly came across bricks, which he began to collect. The results of his collecting and research activities were shown in 1973 at the exhibition “The development of bricks”. The positive response from experts led to the founding of the Vienna Brick Museum in 1978 as a branch of the Penzing District Museum (»Fig. 1). Schirmböck’s collection was donated to the museum. In 1986, the Brick and Building Ceramics Museum became an independent museum.Current director Gerhard Zsutty has been working as a volunteer at the Brick and Tile Museum for over 40 years and has brought together and organised most of the collection.

Tasks of the Brick Museum

The museum has several tasks. One is to document all the brick kilns that have existed in Austria and the entire territory of the Habsburg Monarchy and to collect their products (»Fig. 2). The western neighbouring countries of Switzerland, France and Germany are also included in the processing. At the time of the visit, this collection comprised exactly 13,963 bricks. New pieces are added every week, explains Dr Zsutty. Indeed. Shortly before publication eight months later, the figure was almost 14,100. The growing collection, which is considered to be one of the most extensive of its kind, has been exceeding the capacity of the exhibition rooms for some time. Many pieces have to be stored in the depot. In addition to bricks, the collection also includes roof tiles, chamotte material, stove tiles and mosaic panels. A second important task lies in interpreting and categorising the various signs on the bricks. This is because these are often the only traces left behind by small brickworks that only operated for a few years or decades. They provide information on the place of manufacture, the area of distribution and the time of construction of a brick building. In addition to their function as traces, they are also evidence of industrial and cultural history.

The exhibition shows the history of brick production with a focus on Austria and the brick kilns there, whereby the history of the most important manufacturer Wienerberger forms one focal point, a second the technical and process history of the brickworks and a third the products themselves, the bricks and their symbols. (»Fig. 3)

History of brickworks in Austria

As everywhere in Europe, bricks and the art of brickmaking came to what is now Austria with the Roman soldiers. Bricks were made and used by both the army and private individuals, often veterans trained in brickmaking. The Roman presence lasted from around 50 BC to 450 AD. The Germanic and Slavic peoples who followed did not know brick building and the brick culture in the Austrian lands came to a standstill. In what is now Germany, especially along the Rhine, early monasteries continued brick production and brick building on a small scale after the Romans left, thus maintaining a continuous brick culture. For example, there is evidence that Charlemagne had his palaces covered with roof tiles to reduce the risk of fire. In Austria, brick-making and brick building techniques only spread again in the 11th and 12th centuries in the course of Bavarian colonisation and the associated founding of monasteries.

Brick firing in Austria was a privilege of the clergy, nobility and large cities during the Middle Ages and early modern times. Firing was only allowed to take place in the ovens of the nobility for a fee. The common people were only allowed to air-dry bricks. Private, commercial brick production was only authorised under Empress Maria Theresa from 1775 in order to meet the increasing demand for building materials.

Tracing bricks

The history of brick marks

Brick marks have been used in Austria since the 15th century. The aim of this practice, which was often prescribed by authorities, was to be able to identify manufacturers. For a long time, the quality of bricks was rather poor and often raised the question of the their origin in warranty cases. Often, labelling the year of manufacture was also required, but only a few manufacturers did this due to cost reasons. Emperor Charles VI, for example, issued such a labelling regulation in 1715. In addition to specifying product dimensions such as the length and width of the brick, every brickworks was obliged to display a recognisable mark. However, labelling was not consistently demanded; Charles’ daughter Maria Theresa, for example, did not prescribe it in 1773. A general labelling obligation was not strictly prescribed and argely complied with until the beginning of the 19th century.

Brick marks should not be confused with brick stamps, emphasises Dr Zsutty. The imprinting of a mark on the raw brick using a stamp has been practised since ancient times. In Austria, on the other hand, the bricks were labelled continously by means of mark negatives that were carved or nailed into the moulds.

The marks on the bricks are traces of their origins, the brickworks. “Every brickmaker had his mark. If you walk around the exhibition and have the time and inclination, you can see what brickworks there were in various districts of Vienna,” explains Dr Gerhard Zsutty.

Signs of quality, quality management and invoicing

In addition to information on the origin and year of manufacture, other information can also be found. For example, special privileges such as the status of a purveyor to the imperial court were inscribed on bricks. This was an excellent indication of good quality and thus promoted sales. (»Fig. 4).

It is therefore not surprising that many brick manufacturers tried to either acquire a similar privilege or at least give their bricks a privileged appearance. For example, there are many bricks whose design was inspired by the imperial double-headed eagle: with images of other eagles and birds, even chickens, and even just wings.

Geometric signs, for example, were used to differentiate the performance of different labour teams of bricklayers. They were paid on a piecework basis according to the number of flawless bricks. To avoid disputes over payment, each working group used models with a specific additional symbol of dots or dashes assigned to it. In larger brickworks, Roman numerals were used. Bricks were also marked with counters for accounting purposes, and some even have real accounts on them.

The task of reading traces - understanding and assigning brick signs

Following the trace of the bricks on the basis of the signs is a task of understanding that every archaeologist knows. As with an archaeological find or a papyrus text, the aim is to understand its original meaning. This is not easy: bricks are almost never found in their place of manufacture, the meaning and even the form of signs can change over the course of history, not to mention the use of different languages and orthographies. The meaning of the signs often has to be painstakingly reconstructed. Dr Zsutty explains this task using several exhibits as you walk through the exhibition.

Following the heart

A heart symbol is often found on bricks (»Fig. 5). The first heart symbols appeared in the 17th century and were particularly widespread in the 19th century. However, the origin or reason was unclear for a long time. “There were the most beautiful and romantic explanations. For example, it was assumed that the master brickmaker was in love and therefore drew a heart on his product. Or the heart shape was interpreted as crossed arms. In my eyes, these are very far-fetched explanations. I couldn’t believe it,” admits Dr Zsutty.

The solution came by chance. He found the image of two crossed plain tilel moulds on a brickmaker’s coat of arms. This was a very obvious symbol for a brick manufacturer at a time when letters were rarely used for this purpose. Neighbours adopted the sign with adaptations and changes. One omitted the handles, the next turned it into a pretzel. Zsutty comments on the plausibility of this theory: “Nobody has ever contradicted my theory. And I have already spread it very widely.”

Heart direction

The heart sign itself serves as a clue in various ways. Firstly, a heart sign on a tile allows you to determine whether it is upside down or right side up. This helps to recognise the reading direction and sequence of other signs, especially initials, where the orientation is unclear.

Variety of hearts

The heart symbol can then help to roughly localise the origin of the stone. The heart shapes of the Viennese brickmakers, for example, show characteristic differences to Lower Austrian heart signs. Within Lower Austria, in turn, the hearts from the southern and northern parts differ. This is a great help if nothing else is known about the origin of the brick.

Reading traces

The museum director uses a brick from the Palace of Justice in Vienna (»Fig. 6) to explain how one can proceed following the traces. The brick features images of a compass, square and triangle. As these are classic instruments of a master builder or architect, it can be concluded that the brick came from a brickworks belonging to an architect.

The letters TGY to the right of the symbols very probably stand for the Hungarian words tégla for brick and gyár for factory. This could indicate that the factory was located in Hungary. As bricks were rarely transported far, Zsutty searched for the brickworks on the Hungarian outskirts near Vienna, but without success. Already quite desperate, he remembered that Hungarian was also spoken in Slovakia. From the 16th to the 18th century, the Slovakian city of Bratislava was the capital of the Kingdom of Hungary. North of the city, he came across a place called Bösing (German) or Basin (Hungarian) or Pesinok (Slovakian). This seemed compatible with the letter B to the left of the tool symbols as the initial of the place. He found a brickworks mentioned in the city archives that belonged to a Viennese architect Stefan Krieser. Zsutty interprets the E superimposed with the letter B as an initial for the German word erste (first) or elsö, Hungarian for first. So, according to the conclusion, the brick sign signified the products of the first Bösing brick factory of the architect Stefan Krieser.

For Zsutty, this analytical deduction of correlations is what makes brick research so appealing: “That’s why I put my heart and soul into this job. He can determine 4,000 brick symbols with absolute certainty, while he has assumptions about 4,000 other bricks that he cannot yet prove beyond doubt.

Fishing at the Fischa

Sometimes the search for clues also goes in the other direction, from the location of the brickworks to the drawn brick, as the story behind one of the stars of the exhibition (»Fig. 7) shows. Gerhard Zsutty was looking for bricks from the town of Fischamend, where the Fischa river flows into the Danube. The bricks originally used to build the town were practically impossible to find because the town, as the site of aircraft factories, was the target of heavy bombing raids during the Second World War. After a few unsuccessful reconnaissance visits, he finally asked himself where people throw their rubbish. The obvious answer was in the river. On the banks of the Fischa, he found this brick in a slightly mossy state.

Variety of signs and interpretations

Many other tile signs leave traces in all possible directions. Ambiguous symbols defy simple interpretation, such as the sun, moon, pentagram or swastika, and require broad cultural knowledge. “One very important thing when researching bricks is to empathise with the language and thinking of the people back then, the symbolic thinking, because they thought very much in symbols,” explains Zsutty. He tells of a brick that he was only able to recognise because of his knowledge of a saint attribute. Other bricks require knowledge and experience with different writing and drawing styles. Still other bricks can only be assigned with knowledge of the historical changes in spelling. It is equally important and not always easy to recognise whether a mark on a brick is really a mark and, if so, with what intention it was entered. Some bricks, for example, show markings as if someone had played a board game on the blank. Other bricks show footprints of animals such as cats or dogs. In at least one case, Zsutty believes that a person made this imprint on purpose. (»Fig. 8)

On the trail of brick history

Roof tiles and other ceramic building products

In addition to the marked tiles, the exhibition includes a section on the historical development of roof tiles: from Roman tegula to the medieval pair of monk and nun to interlocking tiles (»Fig. 9). This also includes technical and architectural explanations of this development, for example how the requirements for rain impermeability influence the shape of the roof tile. Or how interlocking tiles were already developed in the Renaissance to reduce weight, but only became established when they came out of machines in regular moulds. A section of the exhibition is also dedicated to other ceramic building products, such as ceiling tiles, special and moulded tiles.

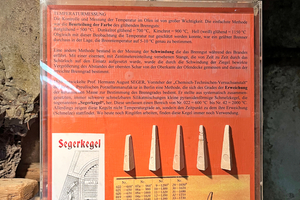

Brickmaking technology

Areas of the museum are also dedicated to the history of the development of brickmaking technology, focussing on the development of firing technology. For example, you can learn how the ring kiln was introduced at the same time as extrusion with a die. Only the uninterrupted production of blanks could guarantee the utilisation of the ring kiln. The industrial production of bricks was only possible with the combination of both instruments. The links between technology and society are also presented. The development of the technical requirements for the mass production of bricks was accompanied by a sharp increase in demand for living space and building materials. The building boom triggered by population growth and especially urban growth in the course of industrialisation in turn made it necessary to standardise bricks. This was because building sites were supplied by different brickworks. The kilns are set up as models and can be viewed.

The exhibition also includes old tools and brick moulds. Zsutty also carries out research here by endeavouring to reconstruct the work steps implied by the objects. (»Fig. 10, 11).

Brick kilns in Austria and the history of the Wienerbergers

The museum’s task of recording brick kilns and the history of brickmaking in Austria and the Habsburg territories would not be complete without the most important Austrian company, Wienerberger. The exhibition shows how Alois Miesbach’s desire to become a brick manufacturer and the work of his nephew Heinrich Drasche gave rise to the world’s largest brick company. The fact that the eponymous Wienerberg was a deposit of marine clay with a high iron content, in contrast to the more calcareous river loam from the banks of the Danube, played a role in this. It is also clear what role Miesbach and Wienerberger played in the technical development of brick production and its spread, for example for Hoffmann’s ring kiln. The social consequences of brick industrialisation are also illustrated by the fate of the “Ziegelböhmen”. Finally, Wienerberger’s contributions to brick development are also discussed. The earthquake-proof brick was very successful, whereas the sliding brick was a flop. Dr Zsutty complements the exhibition with lively and anecdotal stories from the history of the world’s largest brick manufacturer.

Visit to the Brick Museum

The Vienna Brick Museum is recommended to anyone interested in bricks as a craft, industrial and cultural product. This applies both to the exhibits in the exhibition and in particular to the detailed explanations by the museum director. Dr Gerhard Zsutty is not only an expert in his field, he is also very passionate about it. His enthusiasm for the subject is also reflected in his willingness to provide information and is thoroughly infectious.

It is advisable to bring some time with you. The museum is open every 1st and 3rd Sunday of the month from 10am-12pm, closed on public holidays and in July and August. Guided tours for groups can also be arranged outside opening hours by prior arrangement. Admission is free. Instead of a donation, the museum is happy to receive a historical brick gift.

The Vienna Brick Museum is looking for volunteers with previous knowledge. Anyone interested in researching the history of bricks is invited to help with the further expansion of the museum.