TU Darmstadt team of researchers and clinker brick manufacturers revive old technology

Brick shell structures not only have an aesthetic appearance, they can span wide breadths despite small cross sections and carry heavy loads. However, they are expensive to build in terms of both material and labour, mainly because their construction requires an auxiliary substructure of full-face shoring. This “falsework” defines the structure’s curvature and must remain in place until the brick shell is completely finished, since the latter cannot bear any load until the last brick is in place. Consequently, this kind of load-bearing structure is very rarely built.

Developing a computer model

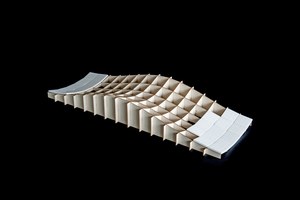

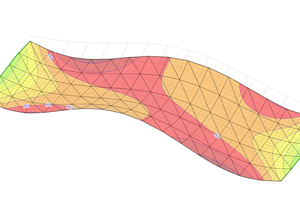

In a research project conducted by the Institute for Constructive Design and Building Construction (KGBauko), Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Sciences, TU Darmstadt, and working within the scope of the research initiative ZukunftBau (future construction), a team lead by Alexander Pick investigated the extent to which brick shells can be built economically – perhaps, for example, by use of prefabricated elements. The first phase was carried out digitally on-screen, followed by real bricks in field trials. The design and calculation of the brick shell were performed with the aid of a computer model. A flexuous prototype measuring 15 m long by 11.5 cm thick was CAD-designed as a 3D model. A complex geometry with rather unfavourable static and structural characteristics was deliberately chosen in order to demonstrate the performance of the principle.

Modularization

“The basic idea of our project”, explains Pick, “is to create a vaulted, curvilinear shape from nothing but flat, square modules.” To that end, the computer model was used to virtually divide the structural system into modules, each consisting of the same number of bricks. While all of the modules are quadrangular and approximately one square metre in size, they were given different angles in order to maximize the freedom of scope for shaping the structure.

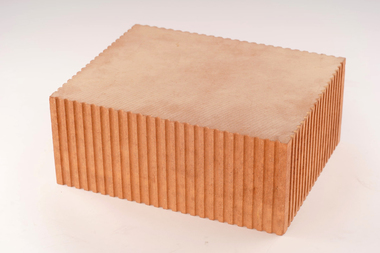

The bricks, too, were analysed by the researchers with regard to the given set of structural requirements. They were designed to yield prefabricated elements with the ability to accommodate longitudinal and transverse reinforcements and enable friction fitting (non-positive) in situ by means of an “overlap joint”. Since the researchers were not trying to install individual bricks, but instead stable, preassembled models, no full-face falsework was needed for purposes of interim support. Next, the individual models were placed on four wooden posts with individually inclined cross sections that were held in place with templates, all of which was effected by means of digitally generate falsework applied directly to the production process. In addition, 1:1 templates produced on the basis of the digital model enabled precise positioning of the finished elements. The resultant offsets between the individual prefab elements were deliberately included as a joining mechanism serving to accommodate the full-length longitudinal reinforcement for geometry optimization.

Reviving an old technology

All details, i.e., the module sizes and angles, the bricks and their configuration, as well as the dimensions and arrangement of the falsework, including its legs and templates, were digitally established and optimized. The computer model therefore not only facilitated the design and sizing of the brick shell, but also made it possible to design an economical substructure for aiding in the construction of the structural system.

In accordance with the digital specifications, the bricks and modules were ultimately produced by, among others, Ziegelei Deppe Backstein-Keramik brickworks and subsequently assembled into the arched, curvilinear overall structure as designed per computer. The thusly built shell structure not only has an elegant, graceful appearance, but also possesses the strength it takes to pass a typical structural system load test.

“As this research project shows, a highly efficient load-bearing structure with an extremely high aspect (or span) ratio and flexuous geometry can be realized by applying the developed method”, says Alexander Pick. The project also showed how a complicated old construction technique can be revived with the aid of a simple new method. Professor Stefan Schäfer, who heads the KGBauko resumes: “We see our expectations confirmed, that this method of construction, one which is becoming increasingly rare due to the high cost of construction, has what it takes to enrich our future architecture.”

Deppe Backstein-Keramik GmbH

www.deppe-backstein.de

Technische Universität Darmstadt

Institut für konstruktives Gestalten und Baukonstruktion

www.kgbauko.de