Quarter 1 on Dresden's New Market

In Germany, the reconstruction of historical buildings and urban ensembles is usually a matter of contention. What some see as 'an architectural Disneyland' is for others the restoration or preservation of cultural essence. Such is the case in Dresden. When the night-time bombing stopped 1945, what formerly was one of the most beautiful cities in the world had been turned into a landscape of ruins. And instead of being reconstructed, the inner city around the New Market (Neumarkt) was transformed into one huge parking lot. But then, Dresden's Frauenkirche, or Church of our Lady, set the stage for a new beginning - with historical façades in the field of tension between modern architecture and modern clay roof tiles of historical design.

Too much history, or not enough?

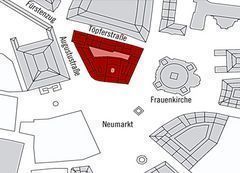

Reconstruction of Dresden's Frauenkirche church was merely the first step. The second: restoration of the OldTown around the New Market and the Frauenkirche. A colossal project in every respect - and an architectural tightrope walk between preservationists, who would have liked to see everything reconstructed; urban planners, who wished to restore the urban environs of the Frauenkirche to the old-established street fronts; the investors, who were looking for a reasonable cost/benefit ratio; and the users and occupants, who expected to gain contemporary living standards. There were eight 'quarters' to be rebuilt. The most sensitive one, located directly beside the Frauenkirche, is Quarter 1 (also referred to as QF, or quarter by the Frauenkirche), an ensemble of what used to be 20 individual lots, but which now comprises 14 buildings framed in by Neumarkt, Frauenkirche, Töpfergasse (~ potters' lane) and Augustusstrasse.

Model structures with Creaton roofs

The architectural firm von Döring was in charge of planning. They solved the Historism controversy with an elegant compromise based on the model-structures principle, which was introduced in the late 1980s as a means of securing an organic bond between old, existing GDR architecture and new buildings . In the optically most sensitive areas, especially along the front facing the New Market and the head-end building on the viewshaft forming the Fürstenzug (literally: procession of the dukes from Saxony), the historical façade ensemble has been re-established by four model structures, with the Weigel House at their centre,. It is only natural that precisely these building fronts are the ones with the best photographic documentation. Hence, in collaboration with the Saxonian Office for the Preservation of Historical Buildings and Monuments, it was possible to rebuild the historical façades true to detail as masonry structures. At less sensitive points, and in cases where the original buildings were either poorly documented or of little architectural value - primarily along Töpfergasse, contemporary architecture now accentuates the visual impression. So while all parts of the resultant ensemble stem from a single source, it now looks like it all grew up over the centuries as an eclectic conglomeration of heritage-listed façades and modern stylistic elements, from roofs with traditional Saxonian 'Kera-Biber' plain tiles and flat 'Domino' tiles of modern design by Creaton, to flat roofs on glass corbie gables. A well-done, seemingly small and clustered counterpoint to the colossal Frauenkirche.

'Kera-Biber': a top product for top architecture

The urban-burgher architecture referred to as Dresden Baroque was characterized by buildings with an average of five floors, with one or two mansard storeys dotted by dormer windows. The traditional roofing consisted of Saxonian plain clay tiles (segmental, with three channels). On the lookout for a type of tile that would come as close as possible to the originals, architect Kai von Döring happened upon Creaton's 'Kera-Biber', a premium tile that is still being produced at a Saxonian clay roofing tile factory in Guttau.

Like all 'Kera' products from Guttau, 'Kera-Biber' are solid coloured and therefore optically robust. Their cut edges look no different than their faces, and even mechanical damage does nothing to change their colour. On the other hand, the tiles' 'high-firing factor' (meaning that they are sintered at temperatures up to 1120°C with no additional sintering aids) makes them so hard and rigid, that mechanical damage need hardly be feared, anyway.

The special quality of 'Kera-Biber' roof tiles is also attributable to the particularly pure clay that Creaton procures in Upper Lusatia and to a production technique in which extra-fine, dust-dry, pulverized clay is mixed with exactly the right amount of water to obtain a homogeneous clay body that imparts a nearly whiteware quality to the end product, with no chance of moisture seeping into the body and causing cracks that can expand when it freezes outside. Nor can moss or lichens find a foothold, and the next rain will wash off any dirt that might collect.

Those beautiful old roofs are back again

What often makes fully reconstructed historical buildings look somehow artificial despite all attention to detail is their lack of historical patina. Real historical roofs draw their charm from the interplay of colour nuances that was once typical of hand-crafted clay products. Nowadays, though, those lively looking, brindled plain-tile roofs of the model structures around New Market Square are full of modern high-tech. Consider for example the 'Golden Ring' at the corner of Neumarkt and An der Frauenkirche. Their intentionally irregular, natural-looking shades of 'mottled-red-brindled' colour and historical character are achieved in a specially engineered firing process that churns out 'Kera-Biber' in numerous different hues and surface finishes. Hotel Stadt Berlin, for example, has a copper-red roof, while some of the others are done in shades of manganese or brown. In any case, those 'Kera-Biber' tiles really caught on with the implementing roofing contractor Mattheus, Dachdecker, Dachklempner, Hausschornsteinkopfbau Dresden-Ost GmbH (roughly: the Mattheus Company - roofers, roof plumbers and chimney cappers, working out of East Dresden), who re-roofed the model structures on Neumarkt, the Frauenkirche and along Augustusstrasse; and Schelzel – Bedachungs-GmbH (~ Schelzel Roof Company), who re-covered the buildings at Töpfergasse 1 – 4.

The 'Domino' effect, or form follows function!

The comparatively unostentatious houses along Töpfergasse, with their contemporary architectural vocabulary, stand in contrast to the baroque design language of the street front facing Neumarkt. The contrast extends all the way to the roof, including the choice of tiles. Here, the smooth 'Domino' version, 'Nuance' model with grey engobe, was chosen for the unassuming, no-frills elegance of its straightforward, stripped-down geometry. In addition to its design qualities, which the neighbours can enjoy from the roof top terrace, these tiles also have great technical qualities: outstanding water conduction and an exceptional Cw value (drag coefficient). These tiles - presently the most plain & simple, straightforward and smooth product the market has to offer - can be used on roofs with slopes beginning at 25°.

New urbanity

Some of the project's critics had misgivings about the reconstructed quarters around the Frauenkirche possibly turning into something of an open-air museum for tourists, but developments since the 2006 dedication ceremony have laid those qualms to rest. Just the opposite happened. In quarter 1 alone, some 50 shops, restaurants and bars, along with numerous offices and even 27 flats (genuine 'living quarters') have breathed new urban life into the district. Once all eight quarters have been restored, the local 'urbanity' probably will have regained its pre-WW II level - before all the terrible destruction of 1945.