The potential to become a new standard work

The Park Books publishing house has published a 208-page book about Zurich‘s brick architecture. It points out that about one thousand brick-faced buildings erected at the end of the 19th century characterise the cityscape of Zurich until today. In addition, the book gives a fundamental introduction to brickwork construction and the manufacture of bricks.

The two authors, Wilko Potgeter and Stefan M. Holzer, both scientists at ETH Zurich, start with a definition of terms: It should be noted, also for the understanding of this article, that bricks and tiles are used as a generic term in masonry construction, meaning the same thing. The word itself does not give any information on the colouring of the stones, on their dimensions or whether they might be perforated.

As local initiation of this building type, the two authors identify the Chemistry Building of the Polytechnic Institute of Zurich (today ETH Zurich), constructed between 1884 and 1886, which back then was deliberately realized as an innovative brick building with exposed masonry. Zurich, already being the biggest city in Switzerland back then, had already expanded very strongly at that time – there was in particular an enormous need of middle-class multi-storey residential buildings. New quarters were therefore developed continuously and primarily realized as five-storey block perimeter developments. Just as it is today, investors came into play, who wanted to present their investments, which were partially not yet sold, already in the construction stage as attractive as possible. Hence, basically the corner houses were built first as a „showpiece“ of the plot. Correspondingly, they featured more elaborate façades than the subsequent buildings connected to them at the road building line.

The background

Potgeter and Holzer introduce the book with the chapter „Vorgeschichte“ (Background) describing the historic beginnings of building with bricks. The chapter is divided into two main topics: For a start, the active building with bricks which they started with the Romans and through the Middle Ages to the beginning of industrialisation. The second subject area deals with the manufacture of bricks, describing the road from the hand-stroke brick, at first air dried and then the fired – or baked – brick to the industrial product. The explanations about the development and functioning of a typical annular kiln for the firing of bricks are tremendously informative as well as the remarks on the colour effects, which are usually caused by the typical way of stacking the bricks in the kiln.

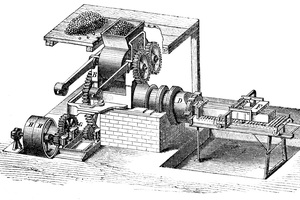

Besides the firing process, they also address in detail industrialised pressing and cutting. This began with the „universal pug mill“ of Carl Schlickeneysen, continued with a horizontal press of Hertel & Co. and found its first perfection in the roller press designed by the Sachsenberg brothers.

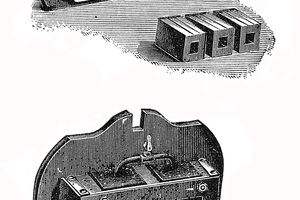

Finally, the explanations of the die used in the extrusion process and the cutting of the still soft moulded clay using wire are essential for the further understanding of the book. In this regard, wear and tear as well as recurring inaccuracies of the machine which are however burnt into the stone and are ultimately used up in building allow its attribution and classification in a non-destructive way even at the object.

Construction documentation by means of photogrammetry

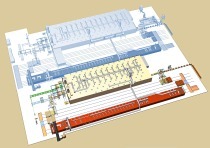

Within the scope of a research project conducted at the Institute of Construction History and Preservation (IDB) headed by Stefan M. Holzer, the team around Wilko Potgeter paid a visit to about three-quarters of the said one thousand facing brick buildings as part of his dissertation on construction methods of brick-faced façades. In addition, the institute created façade sections of about one hundred of the buildings using photogrammetry – i.e., as an accurate and true-to-deformation survey of the wall.

Early beginnings of Zurich‘s brickwork construction

So far, Zurich was hardly considered in the history of brickwork construction. This is a lamentable state of affairs, because, in particular, the city was not affected by the Second World War and consequently the brick-faced cityscape of the centre was left largely intact there. Currently Zurich can be referred to as one of few examples for an urban architecture as it was typical for the German-speaking countries.

Basically, the rich clay deposits in and around the city on the river Limmat had a favourable influence on the brick and tile industry which however was initially limited to the production of roofing tiles. Masonry construction using bricks, however, was unusual in Zurich. The oldest, still existing building of exposed brickworks dates from 1864.

In the second half of the 19th century, the major industrial nations such as Germany, France and England saw an ever increasing proportion of brick buildings. Certainly, this was also noted in Switzerland and ultimately led to the concept of the above-mentioned university Chemistry Building as a facing brick building. More than 80 % of the buildings realized with exposed brickwork are residential buildings, 10 % are public buildings and only a single-digit percentage accounts for commercial buildings. The brick construction boom ceased with the First World War as a consequence of the considerable economic slump caused by the war, which was also true for Switzerland. Afterwards the brick demand recovered temporarily, however was quickly superseded by the changing contemporary taste of the beginning modernity.

Construction types and construction products

About two thirds of the book are concerned with the construction forms and examine the construction products encountered. It is identified that very few buildings – which include above all the very earliest buildings – had been massive solid brick buildings. Quite early, however, a wall system was developed which separated the brickwork into an internal load-bearing layer made of plain solid bricks and a visible facing layer made of high-quality facing bricks. These two layers were interlocking with each other, they were not separated by an insulating air layer, as usual today. Three construction principles have evolved which, primarily for reasons of expenses, more or less replaced each other:

Full-size vertically perforated bricks

As the name implies, the stones are in full size, and are moreover perforated in vertical direction – as is usual still today. Hence their production required less of the high-quality clay types, they even were more lightweight and thus less expensive to transport. The fact that they were also featuring an improved thermal insulation compared to the solid clay blocks, was however not important in those days. Along with the solid clay blocks, half clay blocks and other intermediate sizes were also offered, since splitting them was not an option because of the vertical perforation.

At first, the size of the solid clay blocks was based on the Prussian decree of 1872, that defined dimensions of 250 x 12 x 65 mm, which was however corrected to 250 x 12 x 60 mm by the Swiss Society of Engineers and Architects (SIA) in 1883. This specification was adopted as part of the SIA‘s act of foundation as its first rule ever. But the Swiss measure could hardly prevail specifically for the brick-faced veneer façade, because the so-called „Frankfurt facing brick“ was used here preferably. Because of the large industrial extruders and their permanently firing kilns, these bricks were characterised by a high precision and a very high colour coherence. This facing brick was either bought from the Frankfurt-based manufacturer Philipp Holzmann (predecessor of the well-known construction group) directly – or it was modelled on the same. And, of course, the brick was based on the Prussian measurement. However, experienced craftsmen knew how to adjust the half centimetre height difference within the horizontal joints within the scope of the dimensional tolerances in an elegant way.

Horizontally perforated facing bricks

This type of blocks was also made in an extrusion process, but their perforation is in horizontal direction. Consequently, the wires cut the soft clay column at the narrow sides vertically. The advantage of this was that it was only necessary to realize the exposed brickwork in half the wall thickness of the vertically perforated bricks, with the corner design requiring special bricks which of course were offered in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. The standard horizontally perforated brick had a size of 12 x 12 cm at the narrow side, but for interlocking with the load-bearing masonry it was also available in double wall thickness.

Brick slips

In the last stage of the Zurich brick boom, brick slips emerged which were generally 15 mm thick, imitating a header bond. Generally, they were also produced by the common brick manufacturers, however were frowned upon in the scene and therefore they were usually not shown in the catalogues. In this regard, the authors referred to the parallels of today‘s facing brick slips. They are as well produced by the common brick manufacturers, but they are not communicated in their portfolios and are exclusively offered to final customers through hardware stores.

The former brick slips were a little bit thicker than the present-day, tile-like brick slips. They were likewise made in an extrusion process, extruded as twins with a small connecting web, then split and finally fired.

The brick slips were installed without deep joints. The load-bearing masonry was erected evenly, with a mortar layer being applied at the outer surface. Then the brick slips were pressed into the still soft mortar, and the intended recessed shadow joint emerged by itself. In fact, structural damages are largely encountered at brick-slip façades nowadays. Because especially above the base area long-lasting moisture and frost often blast them off.

Historic postcard series

Ten picture series with historic postcards of the Zurich-based photographer Friedrich Ruef-Hiert are a visual eye-catcher. The book shows 30 of his photographs, which had been taken between 1904 and 1910, according to Saro Pepe Fischer, project manager at the archive of architectural history of the city of Zurich. They were made as postcard templates which in turn were sold by local stationery shops. Remarkably, Ruef-Hiert concentrated solely on the documentation of new development areas, because photos of the city‘s classical sights are totally missing in his complete works. It is a great documentary advantage that Ruef-Hirt himself had provided the photos with the street names in writing. His inheritance comprises about 1000 postcards and was passed on to archive of architectural history by his descendants.

Basic course in brick construction

The hardcover book published in DIN A5 size is written in a way that is also for laypersons easy to understand, building up the contents very coherently and quite comprehensibly. Especially with the general introduction to the history of brick construction as well as the comprehensive explanations on the development and functioning of brick production, the book has the quality of a lecture in the subject area of building construction. The text is brightened up by the rating of contemporary advertisements and historical quotations from newspaper articles. The authors have compared them with findings on site or with additional written sources.

The book exposes the statement that brick construction does not exist in Switzerland as a fairy tale. On the contrary, it indirectly raises the question whether Zurich could not claim the status of a world heritage site for its brick buildings and should not only be recommended to architects-to-be as indispensable reading.

Robert Mehl